Disconnection, the Gospel, and Modern Art

There are many descriptions of art with which I resonate. However, I resonate the most with Dan Siedell’s description of Modern Art as a witness to the Gospel’s promise in the midst of the opposite. It helped me understand the protest I so often see in contemporary art. I’d like to share what inspires me so much about art and disconnection, specifically how the Gospel gives faith in the disconnect. Jesus gives his promise in the face of the opposite, and it always brings life. In my next post, I will share a personal story of receiving God’s comfort through the opposite, in this case our miscarriages, and how and how our comfort was used to comfort others this summer. I hope it encourages you in the opposite you’re in right now.

Dan Siedell is an art critic dedicated to seeing the Gospel of Jesus Christ, as recovered in the Reformation, through Modern Art. In his book, Who’s Afraid of Modern Art?, he notes that Modern Art is about contradiction and juxtaposition. To him, that is also where Jesus’ promises sit: in the midst of the opposite.

“[Modern art] lives in discontinuities. It contradicts our belief that artistic value is found in technical virtuosity, that its “meaning” should declare itself immediately, that looking is easy, and art is about comforting us with what’s familiar.”[1]

For those who don’t know, Modern Art is actually a specific time period of art making. It flourished mid-20th Century, but started with the Impressionists in the late 19th Century. It gave way to Postmodern, Conceptual, and contemporary art (our current period). I had an art professor who jokingly said, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art is where they made the rules; the Museum of Modern Art is where they broke the rules; the Museum of Folk Art (right next to the MoMA) is where they never knew the rules in the first place!” Yet they all make powerful, convincing art that makes you look, makes you think, makes you discover something about yourself.

Edouard Manet, Dejeuner sur l’herbe in the Musee D’Orsay, Paris

One example of the initial pieces of Modern Art that I studied was Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe, which hangs in Musée D’Orsay in Paris. Manet gives the viewer enough perspective to show that he knows how to do it. Yet he has skewed it. The background is too large; it “should” recede into fainter, more blue-gray greens and smaller proportions, if he were following the rules. Thus, Manet’s park and female in the background is right in your face, very forward, flat, immediate. Furthermore, the nude makes you uncomfortable. Everyone else in the picnic is dressed, they gaze at each other or to the side. She, the naked one, looks right at the viewer, as if to question, why are you looking at me? The perspective, the colors, and the nude represent a familiar scene, but it is uncomfortable, awkward. The painting makes you ask, why have I been looking at nude women in landscapes all these years? Why are we doing this? This doesn’t represent me. The artists following Manet began to refuse to represent familiar Greek mythology, Biblical or historical scenes in a way that was classically praised or idealized. People found other ways to idealize themselves. We still do. However, fine art was freed to reveal the wound universal to humanity.

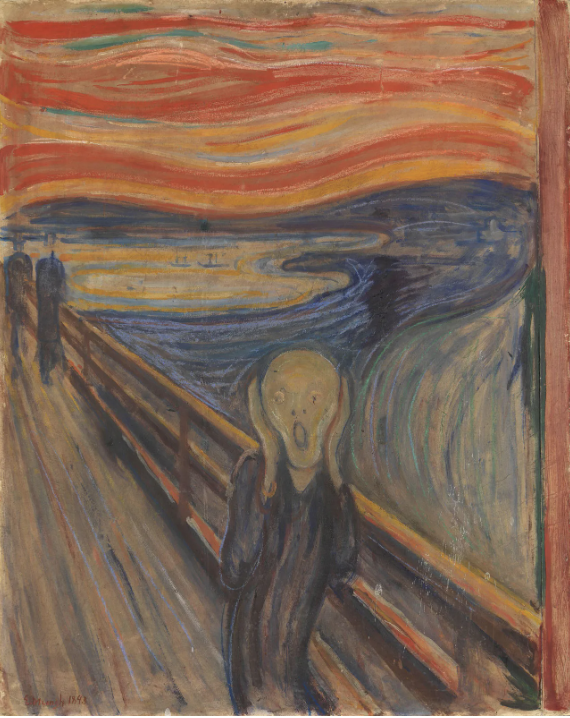

Edvard Munch, The Scream, MoMA

Norwegian artist, Edvard Munch, whose $120 million pastel, The Scream, hangs in the MoMA, said, “Art emerges from joy and pain,” and then he added, “Mostly from pain.”[2] Art pointed to the disconnect between our need for love and the lack of it.

Artists experience the grace of God, whether they know it or not, when they can digest the pain they feel and have it be appreciated by others. This grace is rooted in the Gospel. Jesus has unleashed God’s grace for all those who believe in him. “It seems that faith in the promises of God’s Word actually increases the disparity between the promise we hear – “I am with you always, even unto the end of the age” –and the world that we see: the sickness, death, and injustice. The gospel actually opens up a space for lamentation, for anger, for dismay, for crying out—why? That is the question I often hear in modern art” (Dan Siedell, Who’s Afraid, 10). A true lament, Siedell notes, is only possible when you know Jesus’ promises.[3] You cry out in pain because there’s a doctor to save. In the secular world, you might only hear the pain without hope. In the family of God, you can only face the pain because you have hope.

We would not be able to face our own pain or grief or sin without the forgiveness, grace, and love of Jesus going before us. Indeed, even with Him, we are addicted to numbing, stuffing, acting out! But Jesus never goes back on his word. He kills the old and resurrects the new to life. He makes us face it because he knows the good he will bring from it. And one day, when he makes a new heaven and a new earth, pain will be no more.

to be continued…

Footnotes

[1] Dan Siedell, Who’s Afraid of Modern Art? (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2015), 9-10.

[2] Quoted from Tojner, Munch in His Own Words by Dan Siedell, Who’s Afraid, 9.

[3] Siedell, Who’s Afraid, 11.

[4] Siedell, Who’s Afraid, 22.

[5] Gerhard O. Forde, Justification by Faith: A Matter of Death and Life (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1990), 30-31.

[6] Steven Paulson, Luther’s Outlaw God Volume 1: Hiddenness, Evil, and Predestination (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 241.

[7] Paulson, Outlaw God Vol. 1, 241.