Blessed are those who mourn II

“Blessed are those who mourn” (Matthew 5:4)

The night my father died, May 30, 2020, there were riots in downtown Charleston over racism and police brutality. There had been peaceful marches all week. Sean had marched with pastors to lament the racism and intercede for the reconciling love of Jesus in church and country. The riot hurt the very valid protest in which my husband and I joined. My dad had a phrase, “They’re right about what’s wrong, but wrong about what’s right.” It seemed to apply. Returning violence for violence was so very human. Hurt people hurting people. I’ve been guilty of this. Outside the Roper Hospice Cottage, there was strife and division that night. Yet, in it, mourning united people of every color. Death had brought each of us to our knees. We had a common bond in our pain, in our need for comfort.

The coronavirus quarantine had stopped all gatherings in person. The Roper Hospice Cottage had just opened its doors to 4 visitors at a time when my father entered. He would have died alone had he been admitted two weeks before. For nine days my mother lived by his side as he lay, eyes closed, head tilted, without food or water. His seizures became too much for her to manage at home. It was a relief for us all. His cancer had complicated all our roles; the hospice cottage simplified them. We could just be together.

Death simplified life. I would park my car next to the “beware of alligators” sign just like every other family who arrived to say goodbye. We lined up to have our temperature taken to check for COVID-19. There were Democrats, Republicans, and people of every color, fashion style, and geography. We spoke kind words and shared understanding looks. We all felt for each other. We were losing someone we loved. We all felt the brokenness of this world personally. It connected us in our common problem.

The hospice cottage buffered the noise outside, but there was noise within. The building was very pretty. The halls were airy and filled with Betty Anglin Smith landscapes and other pleasing still life paintings. The hospital beds were wooden, not metal, and gave the rooms a warm feeling. There were gardens all around. Yet it was filled with goodbyes. Our own grief plus the struggle of the dying was loud.

“There can be noise,” the nurses told me. Some of the dying kick, scream, and fight in their fear. They wrestle with the disease until it defeats them. They fear death. I heard some of them when I went to visit my father. It happened to us when he would get a seizure. The nurses would rush in, give him something, and he would quiet down. We would recede to the hall and regroup with deep sighs, tears, whispers, hugs. Even though my father was having as “best an experience of dying from glioblastoma” as possible, even though he had lived a full life, even though he was unafraid to die, suffering death ripped me open.

I hated death. I hated cancer. I hated all the disease that dragged people and their families into this pretty tomb. I hated sickness of all kinds: sickness of the heart, that causes us to hate each other, and sickness of the body that kills health. I hated the racism that killed innocent people. I hated how difficult it is to connect with anyone different than myself. I hated that people died alone because of this pandemic. I hated that my dad was dying. I mourned. I felt the goodness in that, God’s blessing. These are bad things. God hates these things. It is good to mourn. It is better than fighting, better than resenting, better than numbing out, better than blaming. Even though I mourn because I’m losing, I feel united to God, to others who mourn the same. It is a form of repentance, of intercession, of communing with Jesus. That’s why he died as he did.

Jesus’ death on the cross became so relevant. In his death, Jesus gave grace to us. He said, I do not condemn you. I’m taking the worst you do and the worst you suffer and killing it once and for all. We suffer death as a consequence for sin, Romans 6:23 explains. Death infected us all when we turned from God so long ago (Genesis 3). God would not let it separate us from him. He entered into our suffering fully and overcame it. “If we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his” the Apostle Paul promises (Romans 6:5). Jesus died for the victims and the victimizers because we play both roles in turn. I wish knowing Jesus meant that he saved you from the brokenness in this world. That he stopped us from dying, from sinning. He does ultimately. That is the hope of heaven. Yet here, knowing him means that he takes you straight into death and there we find him. There we receive his grace. There he comforts us.

Mourning means I cannot demonize anyone else. I suffer death just like you. I mourn the divisions. I mourn the scars. I mourn the wound. It also gives me compassion when I see others suffer as I do with the effects of death. I lost a great companion in my father. Yet, I gained Jesus’ comfort in a new way. I also gained the fellowship of those who mourn.

If there was no comfort, I could not mourn. The noise would swallow me. Death would win. But there is real comfort because Jesus gives it. He suffered it too. He nailed it and every disease of our heart onto the cross with himself. He died so we might have real hope, real comfort in the face of death. He rose again, meaning death would not be the final goodbye. His comfort knows the pain of death and the hope beyond it. “For the joy set before him he endured the cross,” Hebrews 12:2 says. We were worth it to him. He knows what hope lies in store for those who mourn: “He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away” (Rev. 21:4).

On the morning of May 31, 2020, I heard silence where my father used to be. I so loved going to him to pick up any discussion. He might be watering his garden or at his computer but he would gladly jump right into the topic with me, (the bigger the better), and talk about what Christianity - specifically, what Jesus dying on the cross for our sins - had to say about it. I ached to hear what he had to say that morning. What Bible verse had he thought of in the wake of the riots? What did he think of the coronavirus? Silence. I heard it in from all the places he had led in his life: from the pulpit, the teaching podium, the classroom, the outdoor chapel, the coffee hour, the hiking trail, and my favorite, the breakfast table. The silence was loud. It seemed to honor him. I knew Jesus in that silence. I knew he had my father. He knew my ache. We kept silence together.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

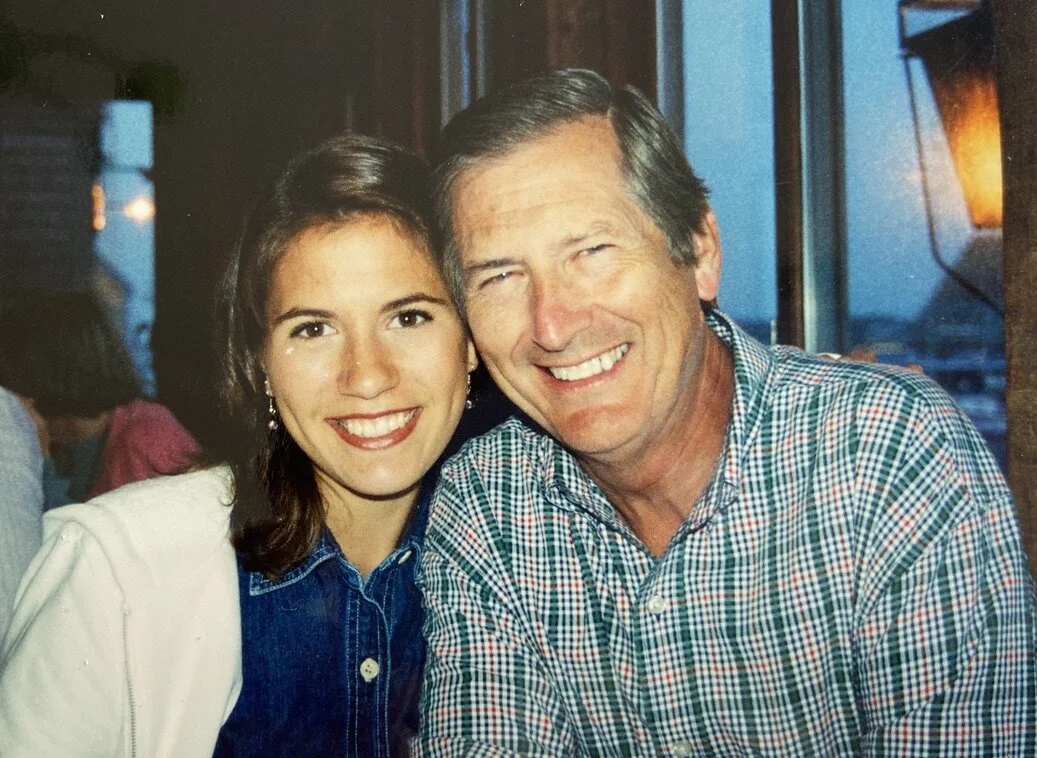

in honor of Peter C. Moore, PeterCMoore.org